Watch the episode on YouTube

Episode Transcription

ALEX: Hi, everyone! Welcome to another LocFact!

LORE: Hi, guys! For today’s LocFact, we will be talking about a game that has sold enough copies to fill a small country, not to mention the childhoods of an entire generation: The Sims.

ALEX: Now, along with the game, a language was created. We’re talking about Simlish. Although the sims weren’t real, their voices most certainly were. The voice actors were in charge of recording arguably one of the most famous fictional languages.

LORE: Absolutely. Simlish was invented by Will Wright, the creator of The Sims. He knew that the game needed dialogue, but thought that using real-life languages such as English would cause the dialogue to be repetitive and would eventually be expensive when it came to translating all of that Sims dialogue.

ALEX: In fact, Wright considered experimenting with Navajo, a Native American language, but decided that it would be a better idea to use a “nonsense language” that couldn’t be translated because the meaning would be left to the player’s imagination.

LORE: Fans say that it may be a mixture of Ukrainian, Navajo, Romanian, Irish, Tagalog, and yes, even gibberish. But that has not been confirmed by The Sims team. Apologies to all you internet sleuths!

ALEX: The Sims has a variety of Simlish phrases that are widely recognized among fans. “Sul-sul” and “Dag-dag” are standard greetings, and Sims often say “Vadish” when saying “thanks.” However, Sims also shorten greetings into just “Dag” or “Sul.”

LORE: Ah, sims… cutting linguistic corners just like the rest of us. Other common phrases include…

CHARACTERS: [Speaking Simlish]

LORE: And sims can even use what’s called the Respectful Greeting or demonstrate the Proper trait to greet each other more politely if they so choose.

ALEX: Simlish is a universal language, and it’s beloved worldwide. You can understand it, but not quite speak it, and it really does help you play this legendary simulation game. We can thank both Wright and also Claire Curtin, the audio director of the very first version of The Sims, for making the magic happen. No one knows Simlish better than they do.

LORE: The Sims even has many renditions of popular songs sung by the original artists in Simlish! Some have music videos created by EA, such as Lily Allen’s “Smile” or Katy Perry’s “Hot ‘n’ Cold.” There are other songs that don’t feature music videos, but they can still be found in various radio stations throughout the game, such as Lizzo’s “Worship” or Kim Petra’s “Malibu.”

ALEX: Simlish isn’t a language with strict grammar rules and a vocabulary. It’s situational, and the only phrases that exist are the ones Sims will use in the game. Players might know some words, but that doesn’t mean there’s a literal translation for everything, or for anything, for that matter!

LORE: Right. And the Sims isn’t just popular in any specific culture or country, it’s a worldwide phenomenon. Chances are, if you’re watching this right now, you’ve escaped reality (at least temporarily) through The Sims at some point. One of the first life simulation video games, it allows players to live vicariously through virtual characters and is played by people from all over the world. The Sims appeals to all of us on a human level, regardless of our cultural background, so it makes sense that the characters speak a fictional language that everyone can understand.

ALEX: Now, on that note, we’ll say “Dag-dag” to you all! Thanks for joining us, and we hope that you hop over to the comments section and let us know what drew you to The Sims in the first place. Was it the lofty goal of owning and designing your own home? Or the ability to wake up actually feeling rested? We definitely want to know.

LORE: Imagine that! See you in the next LocFact!

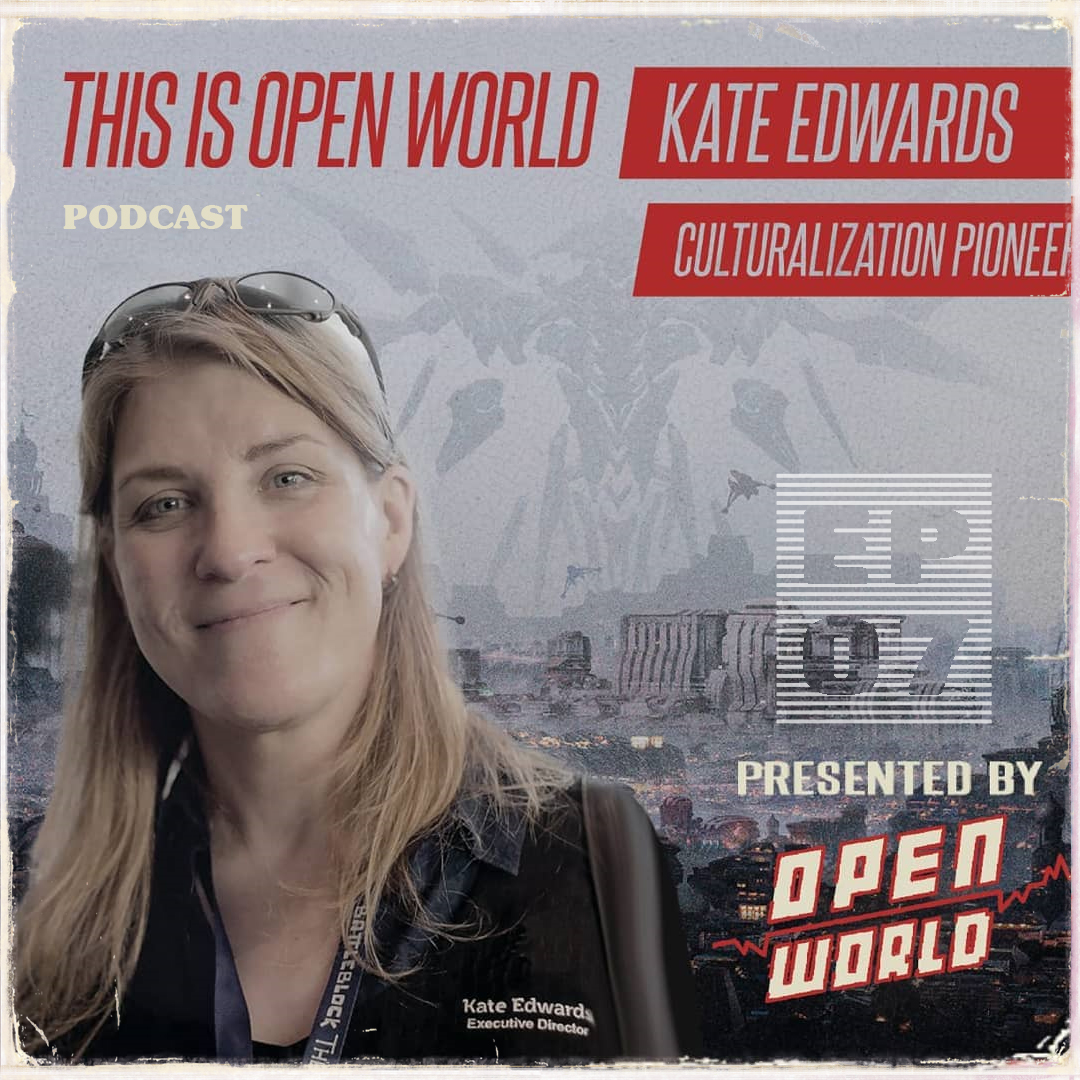

FLOR: Hello, everyone! Welcome to this new episode of Open World. Today, we have Kate Edwards with us. Kate Edwards is the CEO and principal consultant of Geogrify, a consultancy that pioneered content culturalization, and she’s also a board member of Take This, and is the former Executive Director of the International Game Developers Association, that’s IGDA, from 2012 to 2017. In addition to being an outspoken advocate who serves in several advisory board roles, she’s a geographer, writer, and corporate strategist. Following 13 years at Microsoft, she has consulted on many game and non-game projects for BioWare, Google, Amazon, Facebook, and many other companies. Fortune magazine named her as one of the ten most powerful women in the game industry in 2013, and in 2014, she was named by games industry best as one of the six people of the year. In 2018, she was honored with Reboot Develop’s Annual Hero award, and also presented with IndieCade’s Annual Game Changer award. She’s also profiled in the December 2018 publication Women in Gaming among 100 Professionals of Play. She’s worked on many game franchises, including Halo, Fable, Age of Empires, Dragon Age, Modern Warfare, Mass Effect, and many others. Wow! That’s a very impressive background. I mean, we can… We’re so excited to have you here. Welcome, Kate.

KATE: Well, thank you. I would just add… One thing I would add is I’m also currently the Executive Director of the Global Game Jam.

FLOR: Yes. We also know that, and we want to hear all about it because, I mean, how do you do it? It’s remarkable. Honestly.

KATE: I wonder that, too, sometimes.

ALEX: So what can we expect for next year’s Game Global Jam?

FLOR: Yeah. Can you share more details on this?

KATE: Of course. Well, you know, when we had to… When we had our Jam just before the pandemic hit in 2020, it was another record-breaking year for us. We had almost… Well, we had about 49,000 people in 118 countries at 934 live sites, and they made about 9,600 games in that Global Game Jam last year. And then, of course, with the pandemic, we had to pivot to an all-virtual format for 2021, which is something we had never done before. And so that was challenging. You know, it was not easy because, you know, so many people associate the Global Game Jam with that live experience, you know, working shoulder to shoulder with people. And it’s really hard to replicate that online. And so we did our best. Our numbers were down, but we still had about, overall, about 60% to 70% of the people that we had in 2020. So we were very happy about that. We were hoping to get at least 50%, and we easily got that. So, of course, looking forward to 2022, I think all of us are hoping it’ll be on-site again, you know, the pandemic will be past. And I think, you know, most of us will be vaccinated by that point, you know, hopefully. And so we’re, right now, we’re basically expecting it to probably be mostly an on-site event. Although one of the things we learned in 2021 doing the virtual event is that there’s a lot of value in having the virtual access for some people, because obviously some people… well, a lot of people, they live in rural areas and it’s not easy for them to get to the Game Jam sites, that tend to be in urban areas. Or, of course, there’s people with accessibility issues that prevent them from traveling or prevent them from going on a daily basis. So we’re gonna figure out a way to basically, you know, we’ll probably mostly have it live, but we’ll figure out a way to also include people who are virtual.

FLOR: That’s incredible. And I bet that your numbers are going to go up if you go hybrid. Actually, today I heard that Gamescom is going hybrid as well. So I think that’s gonna be the future for most events, right?

KATE: I think so, too. I advise on a lot of events like Gamescom, and I’m on the GDC advisory board and several others. And all of them, I think they all learned last year that, regardless if you go back to an on-site format, you’re gonna have to provide some kind of virtual offer as well.

ALEX: Yeah.

FLOR: Absolutely.

ALEX: Yeah. It’s the new normal. I think.

KATE: It is. I agree.

LORE: The best of both worlds, then.

KATE: Yeah. I think so, too. You know, the biggest challenge there is how do you get… you know, if you can do this, how do you get the virtual people interacting with the live people? Because, you know, they tend to be kind of split. So I think that’s one of the key challenges that events have to think about, is how do you get those two different groups interacting with each other?

FLOR: Yeah. I can’t wait to see what comes up from there.

ALEX: Yeah. It’s amazing…

LORE: Well, another… Yeah. Another question we had for you. We know obviously you are an expert in culturalization, and we wanted to… For argument’s sake, let’s pretend that we are a group of game devs who are working on our first game and we have no idea about culturalization. Not a thing. What advice would you give us to make our game global? I guess more specifically, how does localization complement culturalization in a video game?

KATE: That is a great question. So the way I would put it is that I think, you know, for most people, they understand what localization is. And I think, you know, the way that I see localization is essentially it’s mostly language translation. I know there’s other parts to it as well, but it’s mostly focused on language translation, which obviously is very, very important for making sure your content is legible in other markets around the world. But where culturalization comes in is kind of another level of that, where it’s not focused as much on language translation, what it’s focused is on basically concept translation and cultural translation. So that’s where the culturalization part comes in. So, for example, whereas localization may not focus on the design of a specific character and the outfit that they’re wearing and the symbols that are on their outfit or things like that, that’s what I focus on. So I’m trying to see, are there any cultural influences in the game, whether it’s in the architecture or the character design or even in the story? Because a lot of game narratives will borrow from real world history, for example, but then they’ll dress up the scenario to be something different. So maybe they’ll take like the battle of Pearl Harbor from World War Two, but then they’ll dress it up in a different way. But then it’s like… But a lot of players can say, “Well, I think that’s Pearl Harbor what they’re showing, but it’s between orcs and humans.” So… You know, and that’s the use of allegory. Allegory is a very, very powerful narrative tool that helps us express concepts and ideas in games or film or anything else in a way that kind of… it mimics the real world situation without addressing the real world issue. You know, and some of the older media that a lot of us are familiar with, like the original Star Trek or The Twilight Zone episodes from the 1960s, they were experts at using allegory, because at those times back in the 1960s, you could not show these sensitive topics, you know, explicitly on television. So like talking about racism and talking about the Cold War or all of these kinds of things, and yet a lot of The Twilight Zone episodes, even the Star Trek episodes, they regularly were dealing with issues around racism and issues like that. But they couldn’t say it, you know, and they couldn’t explicitly show it, so they had to do it in a way that was using allegory instead. And so, in games, we do that a lot. In culturalization, that’s one of the things I look for a lot, because culturalization also looks at the narrative as well as the designs, as well as at the overall concept in the world that is being built. And basically my job is to see how compatible is this world going to be with the cultures who are going to be playing in this world? Are there things they’re going to see that may kind of make them not be immersed in the experience? You know, they’ll see something that relates to their culture or politics or something, and all of a sudden, rather than being immersed in the game that you want them to play, all of a sudden now they’re thinking about the real world issue that you force them to see. And so there’s a lot of layers to it, to culturalization, so a lot of different things that you have to think about.

FLOR: Yes. And we also know that culturalization can be part of the whole development process, either from the beginning, when they start working on the lore and the traits on the characters, or at the very end, where the product is finished and you need to go back sometimes to the game developers and say, “Hey, this is not gonna work very well.” So as we already know, you’ve been helping for years publishers and game developers to avoid falling into any political or even cultural or diversity mistakes. But are there any common mistakes that you were able to identify through those years? And specifically when it comes to diversity, in your opinion, what are the games that got diversity right and why?

KATE: Yeah, that’s a great question, too. I mean, you know, obviously things have changed tremendously in all the time I’ve been in this industry, because as of next month, April, it’ll be 28 years I’ve been working in the video game industry, and so… Yeah, I’m old. So… Actually, you know, it’s funny, it’s… I turned 56 last month, so actually that’ll be half my life.

ALEX: That’s pretty damn awesome.

LORE: Happy birthday! And happy milestone.

KATE: Yeah, thanks! Anyway. So, yeah. So in all that time, obviously, the way that we are sensitive to issues of diversity and inclusion has changed dramatically in society, in a good way, you know? I think in a very positive way compared to over 25 years ago. And so that’s really good. I mean, that’s something that I’ve seen that is really encouraging to me, because back when I first started, when dealing with culturalization issues on a lot of the early games, like back in my days at Microsoft, it’s not that people didn’t really care, it’s that they just didn’t see how important it was, you know? So if you raise a red flag and say, why are all these characters white dudes? You know? Now, I’m not saying that’s always bad, because if the narrative demands it, if you can justify that in the narrative, then maybe it makes sense. But then you always have to ask the other side of that question, well, what if it doesn’t matter? It doesn’t matter if one of the people is black? Does it matter if one of the people is Hispanic or another race? And oftentimes, the answer is no, it doesn’t really matter to the narrative. They’re still the same group of characters that are going to go on a certain adventure together. And therefore, that’s where I would push the argument, well, if it doesn’t affect the narrative or the gameplay, then why not be diverse? I mean, there’s nothing wrong with that, you know? And so making that argument 25 years ago was more difficult than today. Well, today it’s almost the opposite. So… Which is great because now companies, a lot of the companies I work with, are being very determined and being very intentional about expressing underrepresented groups in their characters, especially wherever it makes sense. And I think that’s fantastic. And, you know, a lot of the RPGs that I’m working on, like I’m working on Dragon Age 4 right now, there’s a huge effort to make sure that, when you create a character, for example, that you can basically create any kind of character you want, like anything, you know, including variable pronouns or whatever you want. And so I think that’s really the right path forward that gives the player complete freedom of expression within the game’s universe. So one of the challenges that I’ve seen, you know, there’s still… even though things have moved in a positive direction over the last many years, I think just being aware is number one. Some people say, well, that’s the easy part. It’s actually not. It’s not the easy part.

FLOR: If it were that easy, we wouldn’t…

ALEX: We wouldn’t be discussing this.

KATE: Yeah. I mean, all you have to do is go check out Twitter for five minutes and you’ll see that no, the awareness is not the easy part. It’s actually very challenging to get people to come around and understand. And I think it’s… frankly, to be quite honest, it’s more challenging right now than it was even five years ago, because I think we kind of hit this really nice pinnacle of awareness and understanding, but because of the last four years, for various issues that we won’t go into, I think there’s been that greater polarization around these topics. So now you’re getting more pushback from certain people who are just like, “Why should I care about this? Why should I think about this? What about me? What about my rights?”

ALEX: Right.

KATE: You know, it’s just like… The bottom line is like, I still use the same argument I’ve used for many years, which is like, does it change…? For the context of games, does it change the narrative of the game? Does it change the player’s interaction with the world? And almost always, the answer is no, it doesn’t. So better representation does not really affect those things. In fact, it can enhance those things by allowing the player to be in somebody else’s cultural shoes, so to speak, or ethnic shoes or whatever else it might be. So I think one of the things that people need to understand, one of the baseline things, you need to have that awareness and understand that your game is going to go out to a multicultural audience that is global. And I think most game creators want that, you know? They want people to enjoy their game, as many people as possible. And not just for money reasons, because they also, I think all of us as creative people, you make, you spend all that time making something and you want people to enjoy it. It’s that simple. And so, if you want as many people as possible to enjoy it, you have to make sure that your game is going to be accessible from a cultural standpoint to as many people as possible. And so that requires a certain level of awareness. And it also, it doesn’t mean you completely change everything you’re doing in your creative vision, but it means you kind of step back and make sure that everything you’re creating is done so intentionally. Like, why is this object in that environment? Why does the costume look like that? Where did we get the influence from? Why are we borrowing from this culture or that culture? So there’s kind of this level of being very intentional about what we create that is probably, to me, one of the most important things that any developer can do, rather than just kind of get heads down, as we all do, we get in our kind of creative zone and we just make stuff, and then maybe a month later you realize, “Oh yeah, maybe I should not have used that stereotype.” But that’s the problem. A lot of people don’t take the time to stop and think about that. They just keep moving forward and creating.

ALEX: It’s funny because we were talking about one of the LocFacts that we do, and we did the brief and everything, and then we got back to it like a month later and it was like, this is such a good thing that we let it rest, because we could tweak it for a bit, you know?

FLOR: It might be a slight change, but the meaning and how people interpret it and how they perceive what we’re trying to say changes completely. So that part of the creative… it should be like a key for the creative process, right?

KATE: I think so too. And you have to be willing to be critical of your own work. And if you’re not capable of doing that, then you need to have somebody around you who can be. And I don’t mean critical in a negative way. I mean critical, like I always tell people, when I give them feedback, whether I’m mentoring somebody or whether I’m talking to a development team, I will always be constructively blunt, which means I will tell you exactly what I’m thinking, but I will tell you in a way that is hopefully gonna be useful. I don’t want them, you know, to think of this process as a negative thing. You know? And some people, they’re gonna think that anyway. They’re like, “Oh, this is being politically correct, and I don’t like that.” That’s a different issue. That’s a personality and a worldview thing. That’s, you know, I’m talking about specifically what’s best for the game and what’s best for the company and what’s best for the goals of this whole enterprise that we’re trying to do, and keep it focused on that.

ALEX: Right, yeah. What’s best for the game, not what the developer thinks or as an individual thing. But that brings me to something that… I had a hard time phrasing this question. But how do you actually build a world in a video game? Bear with me here, it’s like a multi-layered question. What aspects do you take into account? I mean, you named a few, but to make the player’s experience as immersive as possible. And also, when do you think that’s enough? You’re not like over… Easter-egg everything, you know, or something like that?

KATE: Yeah, that’s… Yeah, that’s a really challenging point, though, I think, every game developer struggles with. And if there’s one mistake I’ve seen many indie developers do is, they overbuild their worlds when they start out, or they just have a vision that is so ambitious that’s way beyond their capability. Or let me put it this way. Maybe they’re capable of it, but not in a reasonable timeframe. So, for example, I once met a three-person indie team who said they’re gonna make an MMORPG. Three people is going to make an MMO…

ALEX: Three people.

KATE: Yeah. And they’re gonna do it with their own game engine that they’re creating. And I’m just like…

ALEX: Ambitious.

FLOR: Ambitious people.

KATE: Very ambitious. I gave them points for being ambitious and being confident, because I think that’s really cool. But also I try to bring a sense of reality to them that, you know, what they’re setting out to do is going to, you know, it’s gonna really be a problem for them in the long run. They’re gonna get discouraged, it’s gonna be a challenge. I’m not saying they shouldn’t try it, but I kept encouraging them, “You need to get more people. You really need to get a lot more people and maybe not do an MMO, and maybe not, you know, not make this massive online world.” It’s like… there’s… don’t do that. So, anyway, world-building, it really comes down to a couple of key factors. And I kind of mentioned them already, but I’m gonna repeat them again. I like to call it “world realization” sometimes. So when you realize a world, it’s basically bringing to life that vision that’s in your head, you know? So writers do it through the written page, and of course filmmakers do it on screen with camera and CG and all that fun stuff. And we do it through game engines and our capability, you know. But all of that process, world-building process at its core is the same. It’s basically deciding, you know, first of all, what’s the narrative you’re gonna tell? You know, every game, in my view, has some kind of narrative. Even Angry Birds has a narrative. It’s super simple. It’s pigs, you know, birds versus pigs, but there’s still a narrative there. And they’ve actually explored that through other media, like, you know, film and comic books and things like that. But in the game itself, there is a narrative, even though the narrative is super simple and it’s right there in front of you, there’s really not much more to it, but there’s still a narrative behind it. And that’s true, I think, of every game. There’s something, some kind of thread of a story that is being told. And I think most people, when we talk about video games, they’re thinking about narrative in the real sense, like Skyrim and Breath of the Wild and, you know, Grand Theft Auto.

ALEX: Yeah, they go big.

KATE: Yeah, huge, expansive narratives that are multi-layered and all these different paths, you know, Cyberpunk 2077 and all that kind of stuff. And that’s, you know, that I think is more typical of what people think about when you think about a narrative for a video game. But the point being is that you have a narrative and then you have the experience. So you’ve got narrative goals, so what’s the story you’re gonna tell? And you’ve got experience goals, what is the player actually doing in that narrative? Is it a first person shooter? Is it an RPG? You know, there’s the genre type, but then there’s also, within that, of course, there’s all kinds of different variables about what kind of things the player is actually going to be doing. And so those two things are kind of the most fundamental thing you have to think about to decide how much world do I need to build to fulfill the narrative goal and the experience goal. And what I see a lot of times is, developers will overbuild because they feel that, in order to create like this full experience for the player, they need to create this, you know, they need a climate system and we need like topography, like mountains and all that kind of stuff. And then we need, you know, an economy and we need a political system, and just all these different things that kind of fill out the world. But I’ve worked on some big games where, for example, they spent a lot of time creating an economy, an in-game economy, like how the economy works in that world, with a money system and everything like that. And then the player almost never interacted with it. And I’m like, what a tremendous waste of time. I mean, because then… because the narrative didn’t really require the player to interact with an economic system, and yet the developers felt that they wanted to have an economic system that was kind of a layered… It was a sub-layer in that world that you don’t really interact with much. But I’m like, why? Why bother? I mean, I understand from a creative perspective that you’re like, “Well, I want this world to have… I want to know everything going on in this world.” But ultimately it’s like, they actually spent time coding an economic system that was never really used. And that’s a complete waste of time, in my view. You know, like, I’ve seen games, for example, building weather systems into their environments. In some of these games, the weather has no bearing on the gameplay at all. It makes no difference. All it’s there is just for atmospheric purposes. Which, you know, which is useful too. But then if you look a look at a game like Breath of the Wild, their atmospheric system directly impacts gameplay. It has a great deal to do with gameplay. Like you can’t climb the slippery rocks when it’s raining and, you know, you know when the lightning is about to strike you, which really sucks. But you know, it’s… But it has that direct impact on you. And so it’s like, was that time well spent? Of course it was, you know, because they actually used that mechanism in the world-building itself. And so that’s one of the areas where I see a lot of developers, they fail right from the start because they just want to make all of this stuff. They wanna make all this really cool stuff to make their world, you know, really kind of fleshed out. But you don’t need to, you know? If you look at games, again, go back to simple games, and some of these, you know, a lot of these tend to be mobile games, but I think we can learn lessons from them. If you remember the game Limbo way back when, that kind of really dark environment and everything, really… they did a tremendous job of establishing the world and the tone and the feeling of the world. And yet they didn’t overbuild at all. They created visually exactly what they needed, and the gameplay itself was fairly simple, you know, side-scroller. But they did a really good job at using kind of a minimalist approach. And yet the game was super popular, did very, very well. And so, you know, thinking that I have to build all this stuff in order to be successful in my game is one of those fallacies that I think a lot of people starting out don’t realize.

ALEX: Yeah. And, while I was listening to you say this, I can remember many games that have these features that you end up not even using. And I’m not going to say any examples, right? But I can I can picture quite a few. Yeah.

KATE: Yeah. You know, I think as players, we always appreciate depth, you know? So I think for a lot of players, they’re not going to turn… You know, like the economic system example. It’s like, if I have a hint of that in the game I’m playing, but I never interact with it, I’m not gonna complain about it. I’m not gonna say, “Why did you build this economic system?” So it’s like I think, from a player standpoint, it’s not wasted time because they have no idea how much time was spent on that, you know? So we’re obviously talking very much from a production standpoint, not from a consumer standpoint.

ALEX: Right.

FLOR: Yeah, but that’s great advice for game devs right there.

ALEX: For devs, exactly.

LORE: And similarly, but also focusing a little bit more on your skills and knowledge as a geographer… By the way, for anybody who has not seen Kate’s video or her GDC talk on world-building as a geographer, I would highly recommend checking it out right away because it is very cool and educational. When you enter into a game world, there are all those little things, or maybe those not so subtle things that tell you where exactly in the real world you are actually standing. And I’m curious, from your point of view, what does the process of coming up with those references look like? Because I would imagine that culturalization, as well as a bunch of market research, must go into that.

KATE: There is. Yeah. I mean, that’s often a collaboration, you know, with several aspects of the team. Obviously, like you said, with marketing, certainly with the game designers. It’s… And being very careful about, where I come into it, it’s like what… Like if they’re going to have some kind of object in the game, like a special object or something, or whatever it might be, a weapon. Who knows? That’s where I come in to make sure that whatever is being added to the game for that purpose is something that fits the universe, it makes sense. It’s not something that’s gonna be seen out of context for that particular world. Unless, again, you have a very specific reason why it’s out of context. You know, it’s… Yeah, so basically, it’s a little bit… it’s that interplay between those areas because you’re kind of anticipating how the player is gonna react to something, but then also you’re trying to stay true to the creative vision. Yeah, but then you also have to be sensitive to the local culture that you’re dealing with. So it’s really complicated. I mean, there’s times on different games I’ve worked on where it takes place in a very clear cultural environment that’s obviously related to the real world. Like when I worked on the Jade Empire game from BioWare, which was years ago, but it was an Asian fantasy world, you know, in much the same way that most fantasy games we play today are based on European Medieval culture. You know, this was the game that was attempting to make a fantasy game that’s based on East Asian Medieval culture, which I thought was really ambitious. And it was super fun to work on this game, but it was really, really complicated because what they did initially is, they grabbed a huge chunk of Chinese culture to be kind of the foundation for the game’s in-game culture. And again, remember, this is not supposed to be related to the real world whatsoever. But then they grabbed pieces of Korean culture, pieces of Japanese culture and a little bit of South Asian, Indian culture, and it’s almost like they threw them all into this big pot and stirred it around and then kind of threw it onto the table and, you know, said, “Okay, here’s our Jade Empire culture.” And that approach was not really the best. I would not recommend that approach, because we had to think a lot more carefully about the objects that we were pulling from these different cultures. First of all, recognizing the fact that just, if you take China, Japan and Korea, there is a lot of socio-historical tension between these three countries, tremendous amount of tension. So we have to be super careful about that, because one of the things that you do when you throw all of these different cultural artifacts into the same pot and then you kind of mix it up and pretend it’s this new culture, it’s like, well, for one thing, you’re saying all of these cultures are equivalent, you know, which is, basically, that’s… In today’s, you know, I think from today’s perspective, that can be seen not only as insensitive, but actually borderline racist, by basically saying like, you know, Japanese culture, Korean culture, Chinese, they’re all the same.

FLOR: Yeah.

KATE: Which is just incredibly inappropriate. So that’s why, when we have games that borrow, you know, objects or we have things that we put into the game, we have to be incredibly sensitive about where we’re getting these things from and what role they play in the game. Especially today. We just have to think very hard about that, not just kind of randomly put stuff in there because we think it’s, you know, we think it’s gonna look good or we think it’s gonna serve a specific purpose for marketing or whatever. Oftentimes, that’s what I call the process of backfilling the game, which is basically when the artists and everybody else doing their work during the main production cycle, they’re just making stuff every day and just throwing it in, you know, just putting all kinds of stuff into the environment. And a lot of times, again, it’s done without as much intention as it should be.

ALEX: Yeah. You have to be mindful of what you’re doing. Again, take a step back, then go back to see if you got it right.

FLOR: Yeah, or have another set of eyes, someone that’s fresh and objective and can bring a new perspective to the table, right? So before we go to our last section, the meme section, I wanted to know, what was your favorite project so far?

KATE: Oh…

FLOR: I know it’s a hard question.

KATE: That is so hard to answer. I’ve worked on so many games. Well, let’s see, there’s…

ALEX: [indistinct 36:42] of your favorite.

KATE: Well, there’s favorites for different reasons. So I’ll tell you the favorite from a very personal reason, and that was working on Star Wars: The Old Republic. So I got to work on Star Wars: The Old Republic for four years and… And it’s not just because I’m a huge Star Wars geek, but it’s also because, when I was… when I left high school, you know, to go out into the world, beyond my first aspiration of wanting to be an astronaut, the next thing I really wanted to do was I wanted to be a conceptual artist for Lucasfilm because I wanted to work on a Star Wars movie really, really bad. And I had the artistic skill, but I just, you know, so I kind of pursued that academically doing industrial design, but then I changed to geography and the rest is history. You know, I could still use my artistic skill with cartography and mapmaking and all that. But that desire to work on something Star Wars was obviously still there. So when I had the chance to work on that game, personally, it was very fulfilling, you know? As they say in Star Wars, the circle is now complete. So… So that felt really good, to be able to work on that. I think from, you know, just from a kind of, more from the geographer side of my brain, working on stuff like Age of Empires has been immensely fun, because you’re dealing with real history and real geography. And, you know, I’m working on Age of Empires 4 right now, we’re wrapping that up pretty soon, and it’s just…

FLOR: Big fans over here, by the way.

KATE: It is fun. I worked on all the original Age of Empires and Age of Mythology, and it was just so much fun to work on those games. It’s also really, really challenging because you have to… it’s a pretty strong intellectual challenge to think about how you’re gonna take this real world event, which was a contentious event, and, you know, put it into a game format that’s going to be, you know, frankly, it’s gonna be fun for players to do this challenge. Yeah, and that can be complicated at times. But they’re always fun to work on Age of Empires. It’s just… it’s such a great franchise. And, yeah, there’s a lot of other games. I mean, I think also from a personal level, just because I’m such a huge fan of the universe, the fact that I’ve worked on several of the Halo games. I’m a huge Halo geek, and when I have extra time to actually play a game, oftentimes, when I wanna relax, I’ll still play Halo multiplayer, you know? I love playing that game. So, yeah, I’m very big into it still. So I think that was also super fun to work on those.

FLOR: We’d love to see you streaming Halo, by the way. Have you ever tried that?

KATE: No, I haven’t. You know, it’s funny because I played really a ton of multiplayer for years and years after the game came out, and then I kind of dropped out because I was busy and everything. And then, of course, I started up again, especially when they finally had the Master Chief Collection on Steam, so it makes it a lot more accessible for me to just, you know, basically not work. I can just turn over here and start playing. But… Which is dangerous. But, um, but, of course, my 56-year-old reflexes are not what they used to be, so. I can do okay, but it takes me several matches to kind of get back into it. If I play maybe five matches, maybe I can get maybe the top five or so. You know, it’s… Now I play it just for fun. The competitive part of it, I don’t think about that as much. Now I just go, if I get killed, “I don’t care.” I’ve been killed many times before.

FLOR: Well, that’s the best attitude to approach it, especially when you don’t have that much time to practice, right?

KATE: Yeah, I don’t. I have very little time.

ALEX: And, I’m sorry, Flor. Before we go to the memes, I want to take one moment to speak about Age of Empires, because this is something that was brought up when we were prepping your interview. I want to thank you, because the amount of things that I’ve learned with Age of Empires, I’ve literally passed tests by doing Age of Empire campaigns.

KATE: Yes! That’s awesome.

ALEX: Literally. So thank you.

KATE: Oh, that’s fantastic. I love hearing that. That’s so cool. Well, it’s the same reason why one of my favorite franchises is Assassin’s Creed. And I have not worked on an Assassin’s Creed game, even though I have advised Ubisoft, but I haven’t specifically worked on Assassin’s Creed. And that would be kind of a dream project for me because I love the melding of history and geography in those games as well. And it’s… they’re so well done. I just have so much fun with those games.

ALEX: You should check out one of the LocFacts that we did. We did a LocFact about the last three Assassin’s Creed, actually.

KATE: Oh, cool! Awesome.

ALEX: About the culturalization of Egypt, of Ancient Greece, and of the…

KATE: Oh, excellent. I will.

ALEX: Yeah, you should check it out. I’m gonna send you the link afterwards.

KATE: Yeah, please do. Awesome.

FLOR: Great. So now we’re gonna go after the fun moment. We’re gonna go to the meme section, because we always like to end on a high note. Yes, here we are. Well, here’s the Star Wars fan. The first one that you shared was a great reference.

ALEX: Now, I could almost imagine one of us getting choked on an interview. It’s like, “How did you say that?”

LORE: One too many questions.

KATE: I think, like many people, I laugh at the dumbest stuff. I thought this was hilarious, though.

FLOR: Oh, yeah. When I was a kid, I was… Because I watched this movie, of course, when I was a kid, and I was so scared of this scene. Now it’s like…

KATE: Oh, yeah, of course.

LORE: Yeah.

KATE: I love it. This one is so dumb, but I laughed so hard when I first saw this. But it’s just… It’s just dumb, but it’s funny.

FLOR: It’s like the dad joke. We love the…

KATE: It is.

FLOR: The Cap’s memes. They’re great.

ALEX: In Greece. I love it.

KATE: So funny.

FLOR: We have a ton of these. I have a lot. I actually have like a special folder of Cap’s memes.

KATE: Oh, nice.

FLOR: I guess we’re with you on this one. Yeah, it’s a thing between some of our team members at Terra.

KATE: Oh, I love it.

ALEX: Well, this is very, very accurate, actually. Now, this is a great movie that I could watch, you know?

KATE: A friend of mine sent me this because he… I know the stuff he collects. And, I mean, look, look at my room. I mean, I collect a lot of stuff, too, but…

ALEX: Yeah, I’m eyeballing that Stormbringer stuff that you have there.

KATE: Oh, yeah. That’s part of my Thor cosplay, so.

LORE: Nice.

KATE: But, yeah, I thought this was really funny. It’s like, this actually is a more realistic version of this film.

LORE: Right.

ALEX: I agree.

FLOR: And this one, too.

KATE: Oh, yeah. No, I like this one. I thought it was a nice, relevant meme here.

FLOR: Yeah. Thank you for bringing this one.

LORE: Absolutely.

KATE: I know there’s people in my circles who would not like this one, but I don’t care.

LORE: Same here.

ALEX: No, we don’t.

FLOR: That’s why we’re sharing it. And we respect everyone’s opinions here. And we appreciate you bringing this because this is also important for us.

ALEX: Yeah.

LORE: Thanks, Kate.

KATE: This one… I showed this one to a friend of mine who collects everything, like… It’s just like, it does not need that extra adapter for that object they threw away years ago. And I just said this to them, because I said, “This is you.”

FLOR: Yeah. I think I have a drawer full of cables.

ALEX: A drawer.

KATE: Of course.

LORE: One drawer? You should see my basement.

KATE: Hey, we’re all guilty of this.

FLOR: Oh, yeah. For sure. Because you never know when you’re gonna need it, right?

KATE: Well, especially in my case, it’s like I don’t remember what it’s for, and I may or may not still have that thing, so I’m like…

ALEX: I might need it.

KATE: Yeah.

LORE: Safer to keep it all.

KATE: Yeah, exactly. Now, this one… This showed up earlier in the year around New Year’s. I thought this was very appropriate. Well, hopefully, it’s not gonna turn out this way, but…

ALEX: I don’t know which one is worse.

KATE: Yeah, I don’t know either.

ALEX: Right? The Joker or It.

KATE: Yeah, I don’t know.

FLOR: Well, it’s already March, when we’re recording this, by the way. Things are looking promising, so I want to see what happens this year.

KATE: Yeah. There’s reasons for hope. Oh, this one, too.

LORE: Oh, my God. I love it.

ALEX: No one sells Bitcoin. So I think that’s the magic of it, right?

KATE: Well… This one… I saw this one floating around whenever it was like, what is it, a month ago or so, during the GameStop stock, when the GameStop stock was being driven upward? And, yeah, people were basically having the same attitude, they’re like, “Take the profits, sell your stock.” And they’re like, “No, I’m gonna hang on to them.“

FLOR: Yeah, well, they tried to do the same with Dogecoin, but it didn’t work.

KATE: Yeah.

FLOR: But that would have been amazing. I mean, the ultimate joke, right?

LORE: Fantastic meme, that’s for sure.

ALEX: Yeah.

FLOR: And that was all for the meme around.

LORE: Oh, no!

FLOR: I know, they always seem so short. Well, thank you so much, Kate, for sharing what cracks you up. Because, I mean, we had a lot of fun with those memes. And thank you for joining us on this new episode. I personally had a lot of fun and I learned a lot. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and your experience with us.

KATE: Well, thank you so much. Thanks for having me here. This was super fun.